Katarina Jerinic spent a month of August in TYPA and this is how she shares her experience here:

While at TYPA, I began a project I had been thinking about for a while in my studio in New York. Tartu is the origin of the Struve Geodetic Arc, a chain of points used to measure the meridian line passing through the heart of the city and stretching far beyond, from the Arctic Ocean to the Black Sea. Nearly 200 years ago, it provided the first accurate dimensions of the size and shape of the planet, resulting in maps that could more precisely describe the Earth’s topography and exactly where you were upon it. As an artist living in the age of GPS, satellite imagery and “street view,” who is concerned with the landscape and ways it is described, organized, altered, built, and navigated, I can’t imagine not having access to this information, even if relying upon it so heavily tends to separate your body and brain from the places around you.

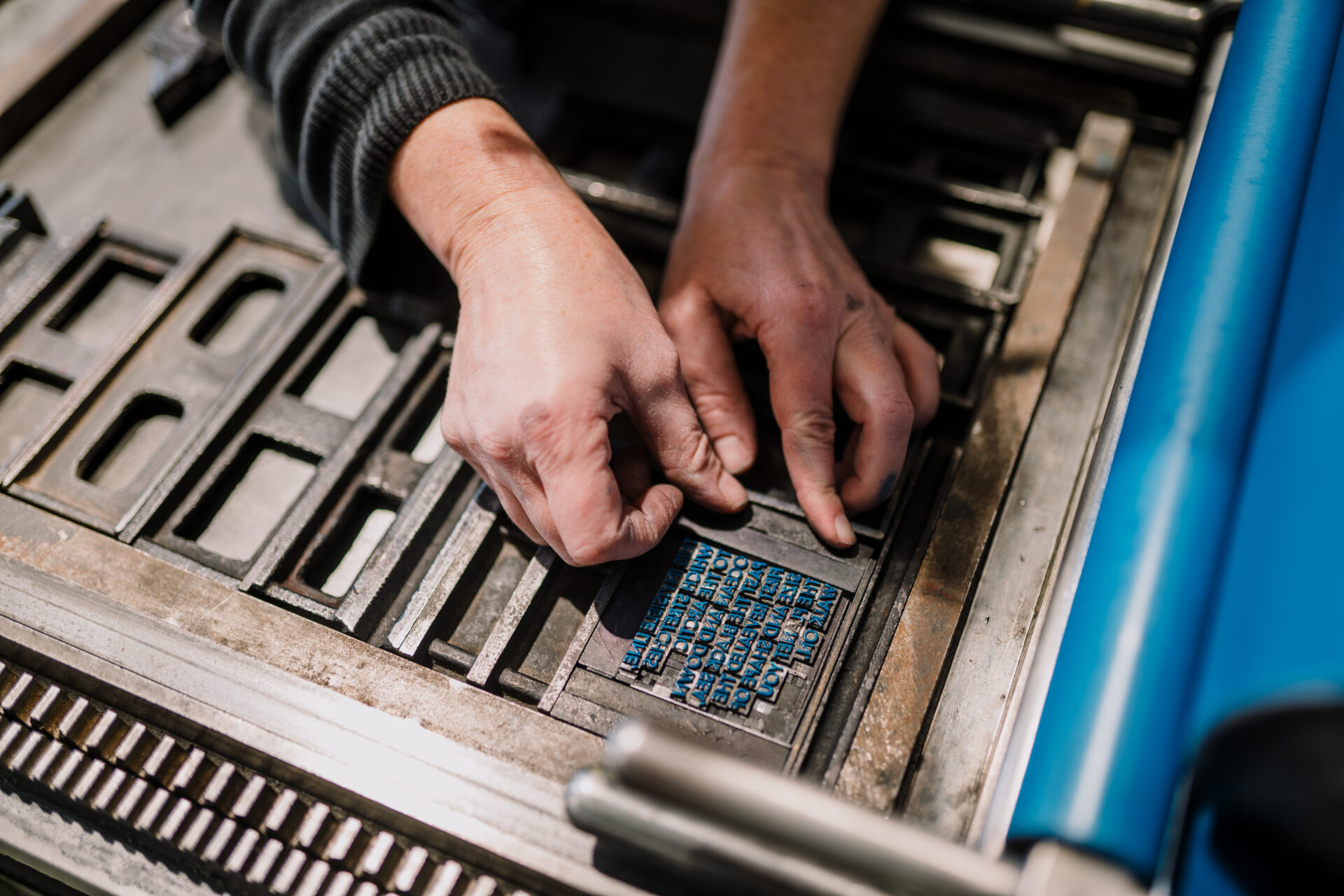

Working at TYPA helped me devise some tangible forms for these abstract musings. I initially thought about my month-long residency as a starting point for a potentially larger project, but I also wanted to finish some work while there and embrace the chance to work with TYPA’s unusual equipment and studio. I wanted to acknowledge the city of Tartu as the starting point of what I consider to be an ambitious, but perhaps invisible, planet-scaled earthwork. I was struck by various 19th century maps of the arc and related topographic surveys I saw at the Tähetorn—the old observatory perched on a hill above the city, which is also the arc’s first measured point—and wanted to make something similar. Using the museum’s various historic letterpress machines, I printed what was declared “the longest cliché anyone has made here” to make an accordion-folded map of the meridian line as it passes through buildings, parking lots, parks and cemeteries in the contemporary city. As I walked through Tartu to make this map, I thought about how such ordinary points in the landscape lead to places much larger and further away and how the significance of a site can be so easily overlooked or unknown. As I walked kilometers to the city’s edges, I also thought about the physical and experiential aspects of exploring a place, which led me to make graphite rubbings of the city’s streets—a form of print-making directly from the landscape to reveal a kind of extremely local topographic map.

As I explored the city according to the arc in these lofty and literal ways, I also thought about Struve himself, who undertook this project to measure the earth. He was both an astronomer and geodesist, engaged in describing two views of our surroundings that seem opposite—sky/ground, above/below—but in fact are deeply connected to how and where we are oriented in space. With this in mind, I made a series of postcards, each featuring a black and white photograph of the surface of Tähe Tn in Tartu, but turned upside down to mimic a dramatic nighttime sky. Plus, these postcards are based on a translation pun: Tähe Tn translates from Estonian into English as Star St.

I appreciated working at TYPA since it is a museum that chronicles the history of print, but also because it’s an active and dynamic place where artists experiment. As I set type, inked presses, and problem-solved printing, I overheard the extremely thorough and generous museum tours given by TYPA’s staff and volunteers multiple times a day. I couldn’t help but think about the revolutionary nature of sharing information, which print first made possible.

In the end, I left maps and postcards for people to take for free, both in TYPA’s gallery and at various points in the city along the meridian line. I’m not a printmaker, but I often realize my projects as printed maps, books or postcards. I’m interested in printed ephemera as a kind of public art that reveals your surroundings and can be put in your pocket to take with you.